U.S. consumer prices increased slower than widely anticipated in January, as headline inflation, i.e. the year-over-year increase in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, eased to 2.4 percent - the lowest level since May 2025. The lower-than-expected reading was mainly driven by declines in energy commodity prices and prices of used cars and trucks, which were partly offset by a 2.9-percent increase in food prices and a 6.3-percent increase in electricity prices. Meanwhile shelter prices - one of the stubborn drivers of inflation over the past two years - eased to a 3.0-percent increase, the joint lowest level since August 2021.

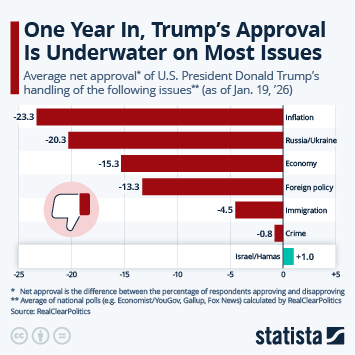

And while President Donald Trump has repeatedly declared victory over inflation in the past few months, claiming more than once that "prices are way down", the latest cooling of inflation shouldn't be misinterpreted as evidence of falling prices. As our charts shows, the overall price level usually knows only one way, and that is up.

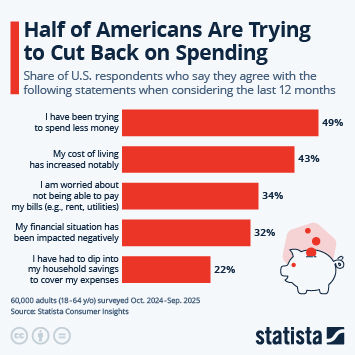

The rate of inflation may have come down significantly from its 2022 highs, but consumer prices have continued to climb and are now 24.3 percent higher than they were in January 2021. With the price level permanently elevated like that, even a moderately elevated inflation rate inflicts more pain on U.S. consumers because the base level of prices is so high.

Whenever we're discussing inflation coming down, it’s important to distinguish between disinflation and deflation. What we’ve seen over the past two years is disinflation, i.e. a deceleration of price increases (yes, increases), or - mathematically speaking - a negative second derivative of consumer prices. For the overall price level to actually come down, the first derivative, i.e. the inflation rate itself, would have to drop below zero, which would signify deflation. While the Fed desperately fought for inflation to decelerate, it is aiming for 2-percent inflation, not deflation, because the latter creates a whole set of problems on its own.