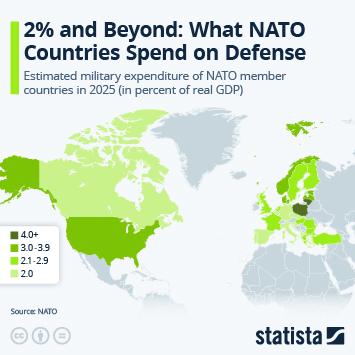

New data released last week by NATO exemplifies how profoundly the realities of foreign relations have changed over the course of the past three years. The military alliance announced that all 31 member nations with armed forces are expected to reach the shared goal of spending 2 percent of gross domestic product on defense this year. Agreed upon in 2014, the 2-percent threshold had been a source of contention within NATO over the years - including during U.S. President Donald Trump’s first term in office - and suffered setbacks as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

However, with the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022 and Trump back in office, the once elusive goal is now marked as realized by the alliance. As suspicion of Russia and China mounts in the West while military superpower the United States is pulling away from international engagements, Europe is undergoing a pivotal moment. This has been dubbed the “Zeitenwende” in Germany, meaning watershed moment or more literally “turning of the times”. As seen in NATO numbers, other European countries also seems to feel the need to up defense readiness, especially those in the continent’s Eastern and Northern parts.

NATO numbers show that at the time of the 2-percent goal’s inception at the 2014 Wales summit, only three member nations were spending the recommended share of GDP on defense. These were the United States, the United Kingdom and Greece, which have all spent more than 2 percent consistently to this day. Maybe more gravely, only four additional nations at that point even spent above 1.5 percent of GDP on their militaries, namely France, Poland, Estonia and Croatia.

Over the years, these numbers crept up slowly to 10 nations hitting the target and 18 in total at or above 1.5 percent in spending in 2020 - still only a somewhat over half of NATO’s members at the time. Numbers largely stagnated in 2021 and 2022 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet, from 2023 onwards, the tables have turned and even chronic laggards stepped up to their self-imposed demands. The biggest leaps in terms of spending between this year and last were done by Luxembourg, upping estimated military expenditure from 1.2 percent to 2.0 percent of GDP, as well as by Belgium (up from 1.3 percent) and Slovenia and Spain (up from 1.4 percent) over the same time period. One non-European nation, Canada, upped spending from 1.5 percent in 2024 to 2.0 percent in 2025, the same as Italy.

Meanwhile, Denmark had already increased military spending from 1.3 percent of GDP in 2022 to 2.0 percent in 2023, while Czechia did so between 2023 and 2024. The Scandinavian nation reached 3.2 percent of GDP in defense spending this year, more than doubling expenditure over the course of three years. It is therefore well on its way towards NATO’s new goal, set this year, of spending 3.5 percent of GDP on the military by 2035. Germany, whose turnaround from a nations reluctant on all things defense to a big reformer in the field has been most closely watched, hit 2.0 percent in 2024, up from 1.6 percent in 2023. The 2025 figure is still outstanding.

The biggest spender in NATO in relative terms is not the United States, which is spending 3.2 percent of GDP on its military in 2025, down from a recent high of 3.6% in 2020. Spending as a share of GDP is already higher in Estonia (3.4 percent), Norway (3.4 percent), Latvia (3.7 percent), Lithuania (4.0 percent) and Poland (4.5 percent) as especially Eastern and Northern European countries continue to grow defense spending fast. The figure also reached 2.8 percent in Finland, doubling in four years, around the same rate as Lithuania’s increase. Both Norway and Poland more than doubled their spending over the three years between 2022 and 2025.