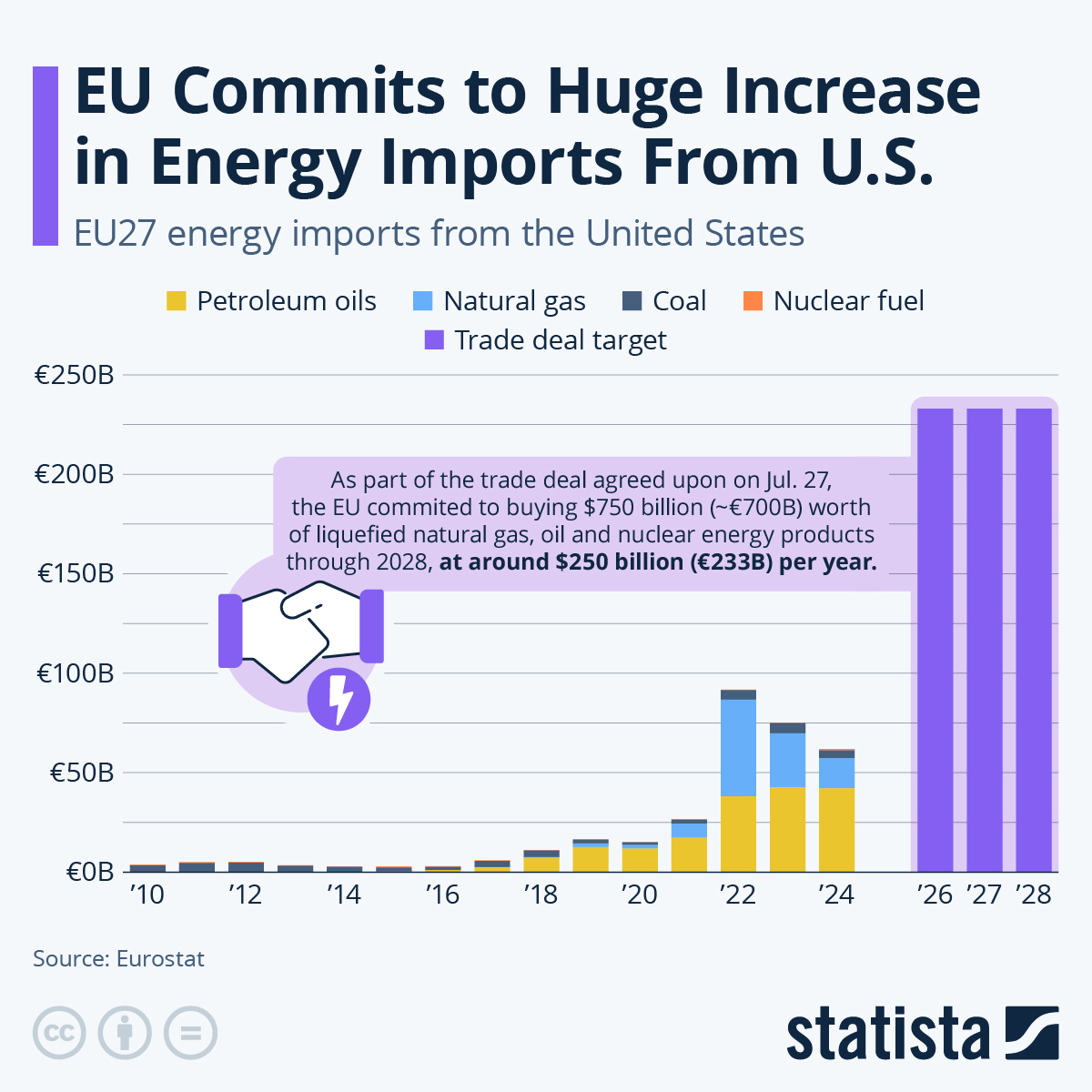

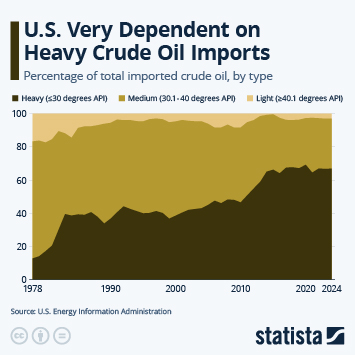

One of the key components of the trade deal that the European Union and the U.S. agreed upon on July 27 is the EU’s commitment to massively ramp up energy imports from the United States. As part of a joint effort to ensure “secure, reliable and diversified energy supplies”, the EU commits to buy U.S. liquefied gas, oil and nuclear energy products worth $750 billion (around €700 billion) over the next three years – a goal that many experts deem unrealistically high.

In 2024, EU member states imported €375.9 billion worth of energy products from outside the bloc, including petroleum oils, natural gas (both liquefied and in gaseous state) as well as solid fuels (coal, lignite, peat and coke). And while the U.S. was already the EU’s main supplier of oil and liquefied natural gas, accounting for 16.1 and 45.3 percent of extra-EU imports last year, all energy imports from the U.S. – including nuclear fuel, which is also part of the trade deal – only added up to just over €60 billion, or less than a third of the annual total committed to in the trade deal.

In a statement announcing the trade deal, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that the agreement would help the EU diversify its sources of supply and contribute to Europe’s energy security. Critics argue the opposite: that the scale of the planned purchases would make the bloc too dependent on U.S. energy after just having successfully reduced its dependency on Russian oil and gas. The deal would also help Europe replace its remaining energy imports from Russia, President von der Leyen, argued, but even fully replacing them with energy sourced from the U.S. would only add around €25 billion to the annual total.

Even if the EU were to try to actually achieve the stated target, which is difficult considering the fact that it’s not the EU but its member states and companies buying the energy, experts argue that it would face insurmountable hurdles on both the demand and the supply side. On the demand side, European energy importers are bound to long-term contracts with other suppliers, making a massive shift towards imports from the U.S. unfeasible over such a short period of time. The same is true for the supply side, where the U.S. would struggle to build the additional infrastructure needed to ramp up exports so quickly and at this scale.

Considering all these factors, the $750 billion figure should be seen as more of a pledge rather than a binding commitment. During Trump’s first presidency, he made a similar deal with China, under which China agreed to massively increase imports from the U.S. In the end, the target was never met and everybody moved on regardless.